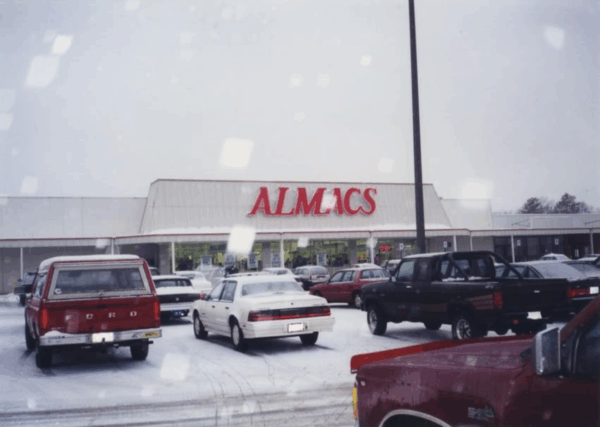

Woonsocket, Rhode Island was once home to many locally owned and regional grocers. There were small stores such as Fernandes Produce and Big D’s. The city also had supermarkets from classic New England chains like Star Market and Almacs.

Over the years, however, the city’s economy took a turn for the worse. Factories closed and unemployment rose. Soon after, the grocery stores began to disappear. The decline was so dramatic that today in Woonsocket, a city of 45,000, there’s only one grocery store–a Price Rite at the edge of town.

Woonsocket is what’s known as a food desert. These are low-income communities where it’s hard to find fresh groceries. According to the USDA, in a city like Woonsocket, this means that many residents live more than a mile from the nearest grocery store. While a mile in a city may not sound like much, according to the latest census information, nearly 20% of Woonsocket’s residents don’t have access to a vehicle. Pair that with unreliable public transportation and suddenly a simple task, like grabbing groceries, can become a real struggle.

It’s easy to think of food deserts as a natural consequence of poverty. But in communities like Woonsocket, grocery stores remained open well into the 1990s, long after the factories closed and the city’s fortunes faded. Stacy Mitchell, a food researcher and co-executive director at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, says the real reason food deserts emerged in poor neighborhoods across the country is because of a major shift in one federal policy.

Robinson-Patman Act

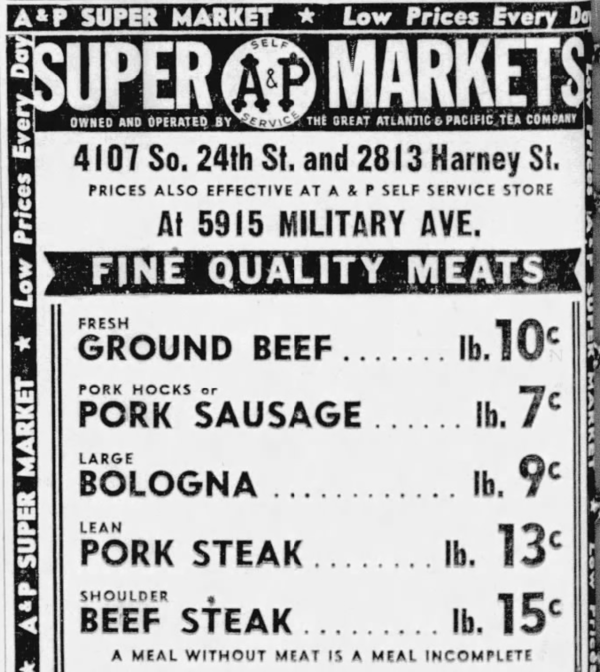

The story of this policy dates back to the turn of the century when one retailer gained a significant share of the grocery market: A&P. The company was once the most dominant retail chain store in America, achieving something no retailer in the country had ever done before, earning more than a billion dollars in sales. At the time, A&P was viewed by many as a monopoly and its size was a massive issue in the country. The company was known to blacklist suppliers who didn’t bend to their will. It also extracted hefty fees from farmers and manufacturers to carry their products. From federal agencies to high school debate classes, people debated A&P and how big is too big.

In response, Congress passed the Robinson-Patman Act in 1936. Nicknamed the “Anti-A&P Act,” this law provided the Federal Trade Commission with a new tool to rein in monopolistic power. For years, the company had used its money and size to push suppliers around and get the absolute best prices on products. When A&P paid its suppliers less, smaller grocers ultimately paid more, essentially subsidizing the discounts A&P received. Economists refer to this as the “waterbed effect,” because when you sit on one side, the other side goes up. But the Robinson-Patman Act changed that dynamic when it outlawed price discrimination. That meant whatever sweet deal A&P received from a supplier had to be the same sweet deal offered to other retailers, including small, independent grocers. After the Robinson-Patman Act went into effect the changes to the grocery business were almost immediate. The law prevented A&P from completely dominating the grocery business by creating a more level playing field. However, in the 1970s, a new school of economic thought took hold. It argued that traditional, FDR-era antitrust enforcement was hindering the American economy, and to unlock America’s full economic potential we needed to rethink antitrust completely. The person for that job? His name was Robert Bork.

Robert Bork

As an academic, Bork was part of a growing movement of scholars and politicians seeking to reshape antitrust in a more free-market direction. In 1978 Robert Bork published The Antitrust Paradox which helped cement a new approach to antitrust. In the book, Bork argues that for decades American antitrust claimed to be about protecting competition and consumers, but in reality, antitrust only protected inefficient companies and punished the successful ones. This “paradox,” he said, actually harmed consumers because it led to higher prices. Instead, Robert Bork steered antitrust so that it focused on what he called the “consumer welfare standard.” This new standard he created focused on low consumer prices over almost every other aspect of antitrust. And to help sell his idea to the public, Robert Bork used the Robinson-Patman Act as his punching bag.

In his writing, Bork called the law, “antitrust’s least glorious hour,” and “the Typhoid Mary of Antitrust.” To him and many others, the Robinson-Patman Act showed how broken and backwards antitrust had become. In the 1980s, Bork’s ideas leaped from the page into the halls of power. Throughout government antitrust positions were filled with appointees who agreed with Bork’s philosophy. The FTC reinterpreted laws and issued new policy guidelines. All of this led the Robinson-Patman Act to stop being enforced. Various administrations, both Republican and Democratic, recognized that the law was a relic of a bygone era. Until recently, when some prominent researchers and legal scholars started to assess the impacts of its retirement.

Lina Kahn

Lina Khan is one of the leaders of the modern anti-monopoly movement. She first rose to prominence after writing a paper titled “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” And as far as academic papers go, it was a real bombshell, starting big debates in antitrust circles. In her research, Lina Khan says that understanding antitrust through Bork’s framework is entirely too narrow because it allowed companies like Amazon to amass power with very little scrutiny. She believed that this level of consolidated power led to unfavorable outcomes not only for consumers but also for society, and one way to clearly illustrate these bad outcomes is by examining what happened to the grocery business.

When the government deep-sixed the Robinson-Patman Act, it was too late for the grocery giant A&P. The company eventually went out of business. But in its place, another goliath had emerged: Walmart. In the late 1980s, Walmart entered the grocery business and quickly took a page out of A&P’s playbook. The suspension of Robinson-Patman created a new incentive in the industry. Who could get bigger, faster? Because the faster you grew, the quicker you could leverage your size over your suppliers. This incentive resulted in a massive merger spree in the 1990s. Large national chains, including Kroger, Albertsons, and Safeway acquired small independent and regional grocers. All of this consolidation devastated neighborhood grocers. The “waterbed effect” was in full effect. Big chains like Walmart extracted discounts from suppliers, and, in turn, suppliers would make up for any shortfalls by charging smaller stores more. Stacy Mitchell and Lina Khan both agree that the decline of small, local grocers and regional chains, paired with the rise of Walmart and other big national chains, has fundamentally altered the food landscape. In low-income neighborhoods, these deep concentrations of corporate power have resulted in food deserts.

What’s Next?

When Lina Khan was appointed Chair of the FTC, she decided to do something no other FTC Chair had done in over 20 years: revive the Robinson-Patman Act. One of the cases Khan filed was against Pepsi, which, by the way, doesn’t just make soda. They are also one of the biggest suppliers in the grocery sector. The case alleged that Pepsi was giving unfair price advantages to Walmart at the expense of competing retailers. Many small, independent retailers supported the lawsuit. In recent weeks, however, Trump’s FTC voted to drop the Pepsi case calling it a “legally dubious partisan stunt.” Khan says that the lawsuit would have helped stop conduct that squeezes small businesses and dismissing it was a gift to giant retailers. The agency is still technically pursuing one more Robinson-Patman case against the biggest wine distributor in the United States, but, given Pepsi, it’s hard to say what the future of that case holds.

Regardless of the lawsuit’s outcome, Khan’s criticisms of Bork’s antitrust ideas have already begun to make an impact. Last year, when courts blocked the Kroger-Albertsons merger, they cited evidence that this amount of consolidation would lead to more food deserts and higher prices. Khan also helped implement new federal merger guidelines, which were retained by Trump’s Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission. That means any merger that crosses the government’s desk will have to meet a much higher standard, not just Robert Bork’s consumer welfare standard.

As for Woonsocket, Rhode Island, several organizations are helping to fill the gaps left behind by corporate America. One organization, New Beginnings, is led by Jeanne Michon, a native of Woonsocket. For a long time, community kitchens like hers have helped feed people who don’t have the means. Over the years, however, she noticed that more people were dropping in who simply couldn’t make it to the grocery store. To help serve these families, she plans to work even longer hours. At the same time, lawmakers in Rhode Island have proposed a package of antitrust laws specifically targeting the grocery industry, including a local version of the Robinson-Patman Act.

发表回复