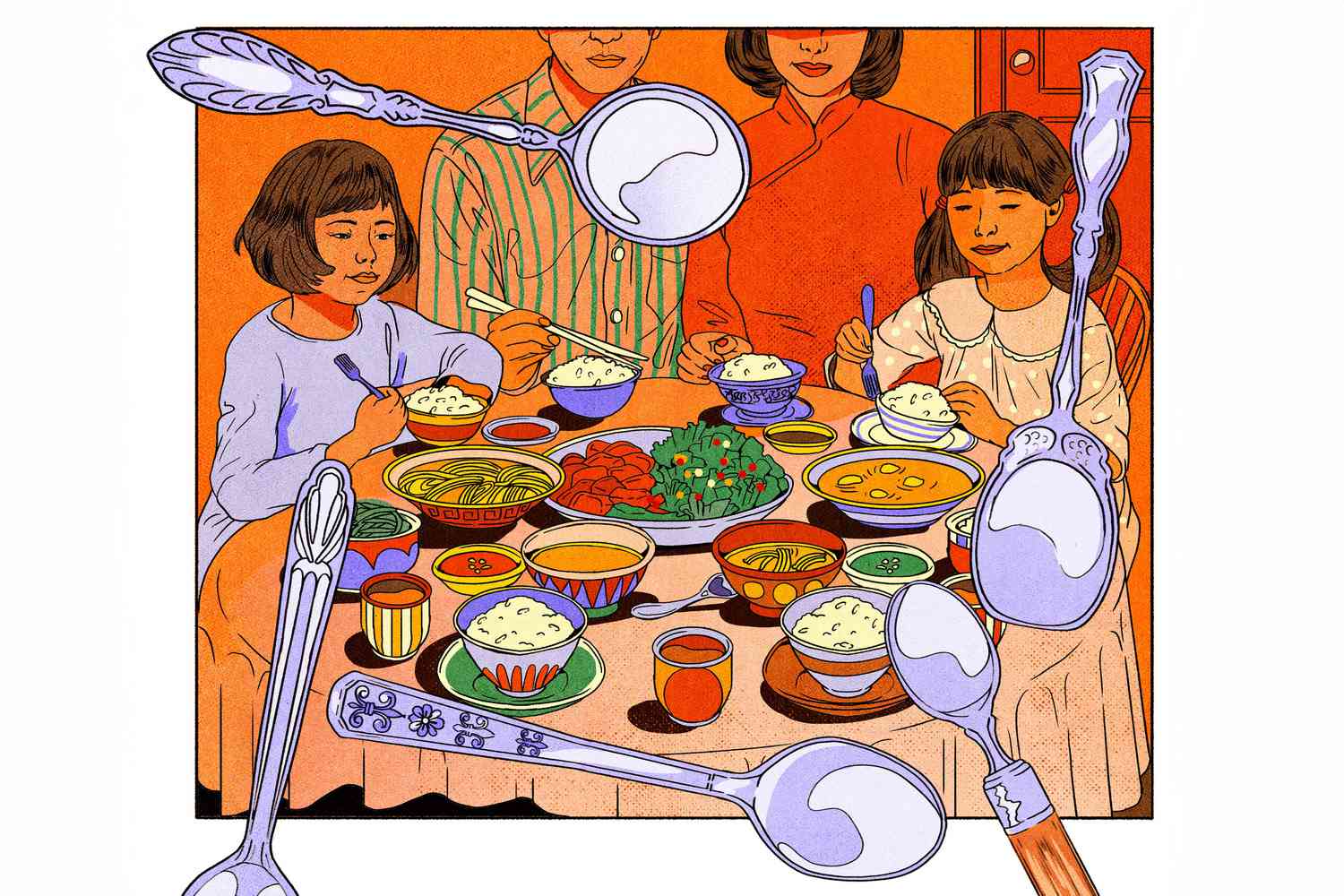

Before I visit my parents’ home, I always get a text message from my mother, Thi, asking me what I’d like to eat. I tell her that anything will do. I know she’ll make something nutritious, filling, and Vietnamese. She and my dad, Danh, will go grocery shopping to pick up enough food to feed a small army even if I’m coming home alone. There will be tons of fruit plates, rice, noodles, and platters of herbs. This is how my parents show their love.

Almost every story my parents tell is related to food. When times were tough, they didn’t have enough to eat. When they were happy, they celebrated with food. When they wanted to show a person that they cared, they fed them. As a child, I was always part of the “clean plate club” because my parents would recount their stories of hunger.

Growing up in a war zone

My parents grew up in Vietnam with war all around them until the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, when 140,0000 South Vietnamese people fled the country by air and sea to escape the encroaching North Vietnamese forces. My father had been a history teacher, and as the government changed, he was tasked with teaching his students how to farm, which he was ill-equipped to do. All of their crops died.

Doan Nguyen

As a child, I was always part of the “clean plate club” because my parents would recount their stories of hunger.

— Doan Nguyen

Both of my parents lost their teaching jobs and struggled to take care of themselves and my older sister. My father worked odd jobs, including selling bread and doing manual labor. Once, while carrying heavy building materials, he found a single grain of rice on the floor and ate it. When he would tell this story, he would say it was the most delicious grain of rice he had ever eaten. They sold their pots, pans, and beloved books to have enough money to buy food. They cooked congee in a small can over charcoal for my sister. All of their stories of this time are about being so incredibly hungry and doing everything they could to feed their young daughter.

Escaping Vietnam on a fishing boat, toward an uncertain future

After several grueling years, they decided that risking death would be better than staying in Vietnam. In April 1979, they pooled money to buy a small, decrepit fishing boat and planned to masquerade as fishermen as they went out into international waters. My mother, father, uncle, sister, over a dozen of my parents’ students, and nearly 2 million of their countrymen left without knowing what lay ahead. Hundreds of thousands of them died or disappeared.

During my family’s journey, three groups of pirates overtook them, stole everything they had, and almost kidnapped my sister. Eventually, they ended up at a refugee camp in Indonesia and they recalled kind people who gave them food, nearly dying of malaria, and having to hunt snakes and frogs to survive. After applying to several countries for asylum, my family arrived in Kinston, North Carolina, in January 1980, with nothing but the clothes on their backs and, as my father says, “Without one single red penny!” I was born nearly a year later.

COURTESY OF THE NGUYEN FAMILY

I grew up with mismatched plates and bowls, secondhand clothes and furniture — the majority of our things were donated to us by the local community. I thought it was amazing when other families owned matching sets of silverware, old cast-iron pans from their grandmothers, and fine china that was passed down from previous generations. It was something that I would never have.

When I was young, I was always jealous when people mentioned an old family recipe or that their grandmother sent them cookies. My grandmother died when my mother was 6 years old, so she wasn’t able to pass on any family recipes; growing up in southern Vietnam, my mother learned how to cook by observing vendors in food markets. I know very little about my grandmother, but I do know that she sold copper pots, adopted a family in need, fled northern Vietnam and — as my mother puts it — “died of heartbreak from losing everything.”

Making my own family heirlooms

I used to long for those handed-down objects and family recipes, but a few years ago, I realized that I do have family heirlooms. I cherish the clothes drying rack that was given to my family. I use it for laundry and to dry freshly made pasta. Of the many things that were donated, we used a set of silverware that had a fleur-de-lis pattern. It’s not fancy or valuable, but I have what’s left of it in my kitchen today. A few years ago, I decided to complete the set via eBay. I now have a dozen soup spoons — a kitchen can never have too many.

COURTESY OF THE NGUYEN FAMILY

When I was an infant, my parents purchased a knife and a whetstone. Every month, my father would sharpen the knife and as a test, he’d see if it could shave the hair on his forearm. With this extremely sharp knife, my parents took turns cooking. My father was on dinner duty if my mother was working a night shift, and my mother was at the stove the nights that she was home. She would often eat crackers for dinner at work to save money, but she would always prepare a healthy meal for our family. I have that whetstone in my kitchen today. I keep my knife very sharp.

And I cook like my mother does, mashing together recipes and gathering information from friends. These days, she’s always sending me Vietnamese recipes or articles about Vietnamese food to show how our culture has gained popularity. Fish sauce is now a staple in so many kitchens, and it’s wonderful that so many people now know what pho is.

I grew up feeling so different, and now I feel a sense of pride. I find it amazing that so many displaced people — especially my parents — took giant risks to better their lives and, in doing so, changed the landscape of food in America. Their courage and the kindness of the people who fed us along the way are heirlooms I will always carry with me.

发表回复