“Yes, your honor,” a teenager answers, her voice barely audible in the quiet courtroom in March. Lakewood Municipal Court Judge Corin Flannigan has just asked her if she understands the charge against her – fighting in public – and the possible penalties she faces.

“I know you’ve spoken to the city attorney about your options,” Flannigan continues. “They are recommending a term of diversion if you choose to plead guilty.”

The girl’s grandmother, standing beside her, hesitates before speaking.

“What happens if she pleads not guilty? She was protecting her property,” she says.

“If you wish to plead not guilty today, you absolutely can, and I will set your case for trial,” Flannigan replies. “Please know that, unlike state court, juvenile cases aren’t eligible for the public defender because no detention or out-of-home placement is possible. So if you plead not guilty, you would either have to represent yourself or hire your own attorney.”

The girl glances at her grandmother. They exchange a brief, uncertain look, and Flannigan asks if she wants to plead guilty after all.

The girl nods.

This scenario isn’t an anomaly. It’s routine in municipal courts across Colorado, where children can be prosecuted for minor offenses without court-appointed legal representation unless they face jail time.

Amanda Savage, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, said the disparity in these cases is profound.

“There is such a power imbalance any time an individual is in a courtroom, even if they are represented,” Savage said. “You have the power of the city or the state on one side against a single person, even if they have an attorney. And that’s so much more dramatic when it’s a child or a young person, especially when they are standing there by themselves.”

The harsh reality of youth in municipal court

Thousands of Colorado youth receive municipal citations every year, often for school-related incidents such as fighting, disorderly conduct or petty theft.

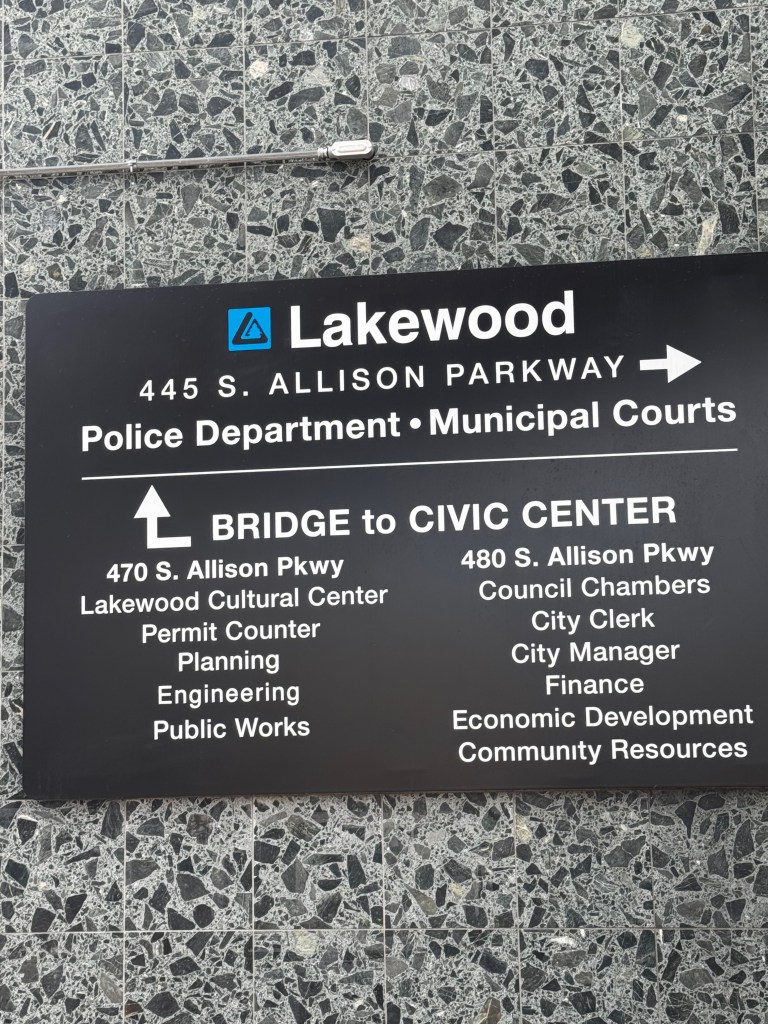

According to a 2025 National Center for Youth Law report, Lakewood Municipal Court alone handled over 8,000 youth cases between 2016 and 2022, many of which originated from school-based incidents. The report found that only 1.5% of these cases involved a defense attorney, meaning nearly all children were left to defend themselves.

Not only do the vast majority not have an attorney, but the report highlighted just how young many of the defendants are. In Lakewood, 36 cases involved 10 year olds, 98 involved 11 year olds and 278 involved 12 year olds, most of whom faced court involvement for minor, child-like misbehavior.

Hannah Seigel Proff, a defense attorney representing youth in municipal and state courts across Colorado, said that this pattern of prosecution unnecessarily entangles young children in the legal system and imposes excessive supervision for behaviors that could be handled within families and schools.

Proff believes this over-supervision of youth who don’t have significant risks or needs is problematic.

Savage agreed, describing the lasting impact this can have on children’s futures.

“It can certainly set people on a path that involves increasing levels of involvement in the system,” she said. “If they don’t do well while they’re on that diversion or that probation, it can get longer, additional problems can crop up from it, and it can become a big part of that person’s life and future identity.”

A courtroom stacked against kids

Proff emphasized that the system places an undue burden on children and their families.

“You have a system that is designed for adults being applied to children with no modifications,” she said. “You’re putting children in front of a judge and a prosecutor, without counsel, and expecting them to understand their rights, their legal options and the long-term impact of their decisions.”

Credit: Shutterstock

Proff noted that many of these children have no way to obtain legal representation.

“In municipal court, they give you a piece of paper with a list of low-cost lawyers, but most of those lawyers don’t take these cases or won’t return calls. So in reality, these kids have no representation at all,” she said. “Without legal representation, families do not understand their rights. Prosecutors downplay the severity of the municipal court system, but these cases are often the first stop on the school-to-prison pipeline.”

The report also highlights another stark disparity – youth in municipal court must pay for discovery, which is the process of obtaining evidence against them. In contrast, evidence is freely available to juveniles in state court. This financial barrier means many children never see the evidence being used against them before making critical legal decisions.

The report also argues that prosecutors often encourage youth to plead guilty and enter a diversion program, regardless of whether they fully comprehend the long-term consequences.

In Colorado’s juvenile justice system, diversion is an alternative to formal prosecution. It aims to prevent further legal involvement by requiring youth to complete certain obligations, such as community service, restitution payments or educational classes, in exchange for dismissed charges.

While intended to keep youth out of the court system, diversion still carries significant financial and time commitments that disproportionately burden low-income families.

Proff said she’d seen the push for families to accept diversion programs – without the families fully understanding the consequences – play out many times.

“What has become clear to me is that the majority of juvenile municipal dockets are kangaroo courts,” Proff said. “Most children are unrepresented, and prosecutors push them to accept diversion sentences before carefully reviewing the facts of the case.”

A guilty plea can also have negative consequences concerning immigration status.

A YouTube video advising Lakewood juveniles of their rights states: “a plea of guilty or finding of conviction or possibly just the charges themselves could affect your immigration rights. You could be deported, you could lose your ability to become a naturalized citizen and it could affect your ability to return to the United States if you were to leave the United States.”

Punishment beyond the courtroom

The consequences of municipal court involvement extend far beyond a single court appearance. Youth can face fines and fees as high as $2,650, which the National Center for Youth Law report notes are amounts they often cannot pay.

Parents, too, are drawn into the process, sometimes held financially responsible for their child’s penalties or are required to accompany them to community service, court dates or probation meetings, according to the report.

Savage also noted that the burden doesn’t just fall on the child.

“There’s such a huge impact on the whole family when the kid has a municipal court case,” she said. “Because not only does the young person have to be there, but the parent does, too. That means the parent is missing work. The fact is, the parents also have to disrupt their lives and spend time doing this, instead of spending time at work or with their other kids or doing productive things.”

Who benefits from this broken system?

The National Center for Youth Law argues that Colorado’s municipal court system disproportionately impacts low-income families and youth of color, indicating that schools in lower-income neighborhoods are more likely to call law enforcement for behavior that could be addressed through school disciplinary measures.

The report found that at least 22% of youth cases in Lakewood stemmed from school-based offenses, highlighting a school-to-municipal court pipeline that disproportionately affects students of color.

The data also showed that the three schools referring the most students to Lakewood’s municipal court have some of the highest percentages of Black and Latino students in the Jefferson County school district, reinforcing concerns about racial disparities in school discipline.

Proff said this disproportionate referral pattern raises concerns about how disciplinary decisions are made and whether schools rely too heavily on law enforcement for matters that could be handled through alternative interventions.

She pointed to Littleton’s restorative justice program as an example of an approach that, when implemented thoughtfully, can provide a more meaningful alternative to punitive measures. Proff was particularly impressed by the program’s restorative justice circles, which offer youth the opportunity to engage in community-based resolution rather than facing legal consequences that may not fit their situation.

However, she also noted that restorative justice should not be applied as a one-size-fits-all solution and that careful consideration is needed in determining which cases are appropriate for such programs.

The fight for reform

In December 2023, Denver City Council unanimously approved a bill to provide free legal representation to minors between the ages of 10 and 18 who are facing municipal violations. This initiative, which took effect on July 1, 2024, ensures that youth accused of offenses such as alcohol possession, trespassing, theft and minor assault receive appropriate legal counsel.

Credit: Shutterstock

However, Denver is currently the only county in Colorado offering public defenders to minors in municipal court settings.

The National Center for Youth Law is now pushing for similar reforms statewide, calling for automatic legal representation for juveniles facing charges in municipal courts.

The center recommends that policymakers enact legislation to eliminate youth fines and fees, raise the minimum age for prosecution, mandate legal representation for minors in municipal court and require comprehensive data collection on ticketing and court outcomes.

The center also urges police departments to limit or discontinue issuing tickets for school-related offenses and shift discipline away from the legal system.

For school districts, it’s calling for revising disciplinary codes to reduce student ticketing for minor infractions and adopting restorative justice practices to address conflicts that promote accountability and resolution without legal consequences.

Proff believes that the question of whether children should be expected to navigate the complexities of the legal system without an attorney is one of fundamental fairness.

The presence of a lawyer can significantly change how a young person experiences the legal process, Proff said, helping to demystify the system and ensure that youth feel heard and understand what’s happening.

“Even if the result is the same, even if a kid decides to still take a diversion at the end of things, just having a lawyer there and feeling like it was a fair process has value,” she said. “It makes it less scary. It helps people understand what’s going on.”

She added that many people are unaware that children can be prosecuted without legal counsel — a reality that often comes as a shock.

“The fact that a child can face prosecution without legal counsel is something that shocks most people when they hear about it,” Proff continued. “It just feels really backwards.”

发表回复